Rolling the Tape: Memory, Music, and Creative Roots in the West

Gifted by William Bowling

Gathered by Nancy Small

Laramie, June 2025

William Bowling reflects on a life shaped by music, beginning with childhood performances alongside his concert violinist father in Colorado. Through candid stories of artistic pressure, family legacy, and economic struggle, he shares how he rediscovered his love for the violin and creative expression in Laramie, Wyoming. From makeshift busking to dedicated studio space, Bowling’s story is a testament to the enduring power of art, memory, and place.

William Bowling:

I’ve always believed that you should start recording from the minute someone walks in the door—especially in musical settings—because you never know what’s going to happen.

We still say “roll the tape,” but of course it’s not tape anymore. You don’t have to change reels—it’s digital, and basically free now. I was just in a recording session a few weeks ago over at Will Flag’s place—he’s one of the recording engineers on campus, but he’s also got a home studio. He was recording a band I’ve played with, and I’m pretty sure he was secretly keeping the recorder running the whole time without telling us.

Because you always end up catching things you wouldn’t otherwise—stories, conversations, even musical ideas. And if you didn’t hit record, you missed it. And it’s hard to have someone retell a story. Once they know they’re performing it, the spontaneity is gone.

It’s funny—I teach theater to kids, and we do a lot of improv exercises to help them with creativity and storytelling. But then, after they improvise, they’ll try to re-create what they just did, which is kind of the opposite of what the exercise was for. Still, it gives them a chance to show off, and that has its own value.

Anyway, I keep coming back to music, because that’s what grounds me—and it’s also what makes me feel connected to Laramie and Wyoming. I’ve got a few threads in my head right now, and I’ll try to pull them together.

So I was telling you earlier about my dad. I grew up in Louisville while he played violin in the Denver Symphony. My earliest memory of him is from the peanut gallery at Symphony Hall.

I’m pretty sure the house I grew up in burned in the Marshall Fire. I left when I was really young, so I don’t have a strong personal connection to it anymore. But I still think about it—because that’s the place where my memories first started to form. Now, watching my 2-year-old niece and my baby nephew, I think about that: where will their memories start to become cohesive?

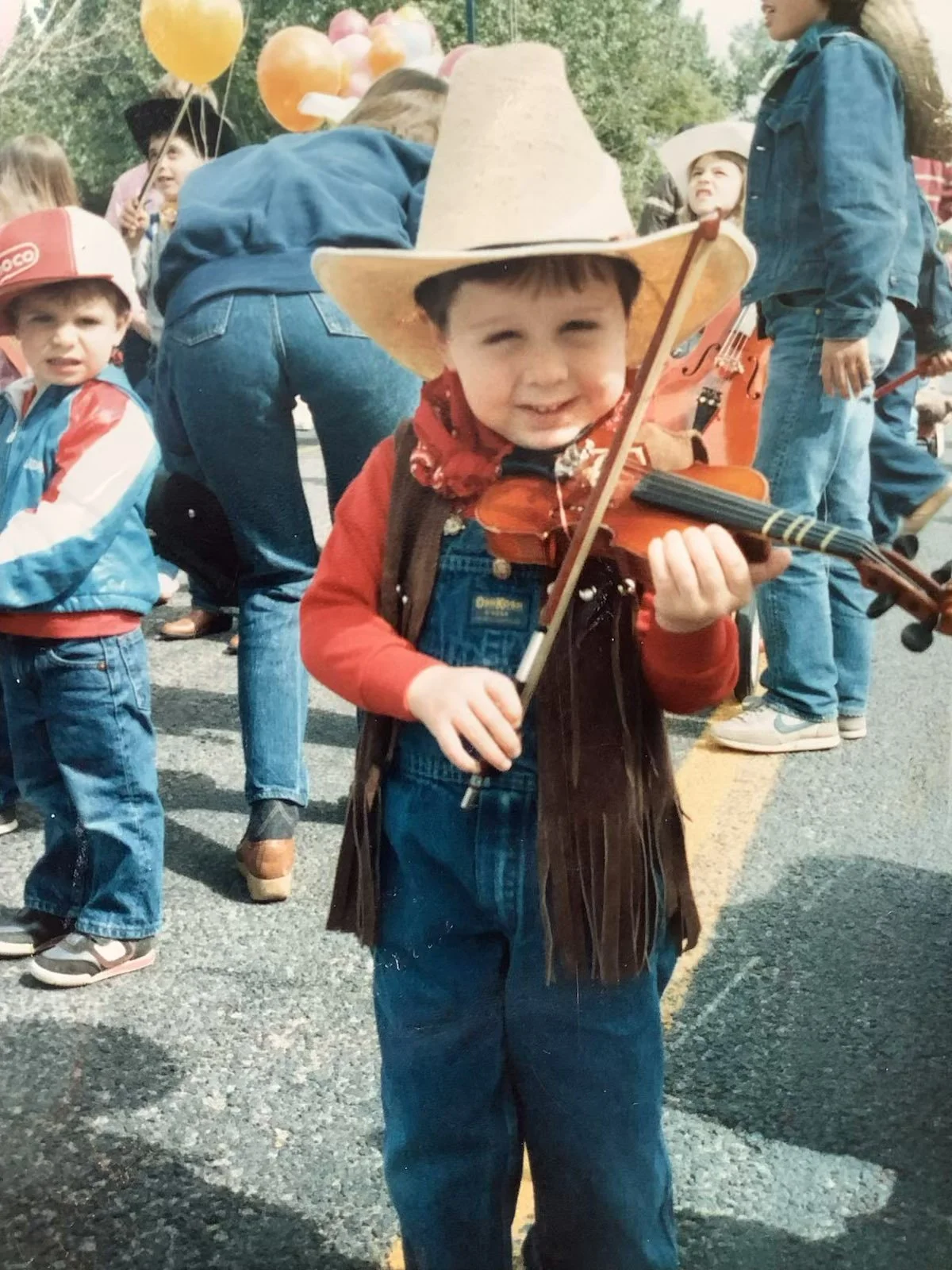

My dad is still the best musician I know. He instilled that love of music in all three of his sons. I’m the oldest, and we all started learning violin around age five. You get this tiny Suzuki violin—it’s about this big [gestures].

I think, like a lot of men from his generation—he was born in 1952—my dad broke a cycle of trauma that existed in his family. His father and grandfather both struggled with depression and, at times, violence. But my dad moved into something I’d call a more mature masculinity—centered around art, culture, emotion.

He’s an awesome guy. But like a lot of fathers, he also wanted to build his sons in his own image. So, if he was a musician, his sons were going to be musicians.

Because I was the oldest, he was most strict with me about practicing. A little less strict with my middle brother, and least strict with the youngest. Turns out, the youngest is the best musician—probably because he felt the least pressure.

When I was thirteen, I’d say, “I want to go play with my friends,” and my dad would say, “Practice your violin first.” And that just made me want to do it less.

Another early memory: we were pretty poor when we lived in Louisville—bare-bones. You might not be shocked to learn that violinists in symphony orchestras don’t make much money, especially with three young boys.

So my dad would go busking at the Boulder Mall—that big outdoor pedestrian mall. He’d play these amazing classical pieces and sometimes come home with only $4 after four hours. Eventually, he realized that if he brought me with him—me and my tiny violin—we’d draw a crowd. So he’d nudge me and say, “Okay, go now!” And we’d play together.

It wasn’t until I was older, when we were living near Chicago, that I realized: that’s how we bought groceries. That’s how we got by.

Later, I had a complicated relationship with the violin. In my teens, I think I was rebelling against my dad, against that pressure. It felt like it was something he wanted me to do, not something I chose.

But as I’ve grown older, I’ve come back to the instrument in a different way. It’s not just a musical object—it feels like it carries family lineage. And I’ve found ways to use it artistically that I never imagined: in theater, performance, composition. Now it’s something I treasure. I use it every day.

I’m lucky to play with a great band in Laramie—The Great J Sjogren. I get to play fiddle for him, which is pretty awesome.

One of the things I really value about living here is that I have access to creative space. Aubrey and I share a studio in the Laramie Plains Civic Center. We each have our own areas, and a shared space too. I’ve never lived anywhere where I could afford a third space—just for creativity.

And somehow, I can afford that here. I go there almost every day to play the violin. It’s a place just for creativity. That’s rare.

In Wyoming, you find creative spaces everywhere—not just in buildings like the Civic Center, but on mountaintops, in the high desert. There's a special kind of creative energy here. I’ve felt it in other places too, but it had started to dwindle. Maybe it was environmental, maybe economic. But here, I’ve felt it come back.

My earliest memories of creativity began here in the West—and now, they continue here in the West.